Henry Scott Tuke (1858-1929) The Critics 1927

Recently someone asked me if C.G. Jung thought homosexuality was a mental illness. The short answer is, emphatically, no, no, no! Jung was not that categorical about anything. Even though he was from a time when it was not yet socially accepted, to Jung homosexuality was not necessarily problematic. For Jung homosexuality was even the spiritual destiny of some people.

To Carl Jung, homosexuality as an expression of one’s true nature is about relatedness and love, and like all love relationships, homosexual love can have problematic expressions.

Let’s be clear from outset, lest anyone’s righteous feathers become indignantly ruffled by anything in this post. First, I am answering a question about Jung’s ideas concerning homosexuality.

Second, if I say anything about homosexuality as a neurosis, I don’t mean anything particular to homosexuality. Neurosis is non-discriminatory. When it comes to expressing our sexuality, neurosis can affect any of us.

Love is a force of destiny whose power reaches from heaven to hellCarl Jung

Even when Jung wrote or spoke about homosexuality, he never said much. He does intimate a lot though, and we can certainly work with that. For those who are interested, in the specific works of Jung, homosexuality is mentioned in Dream Symbols of the Individuation Process and the Zarathustra Seminars, as well as throughout the Collected Works. Robert Hopke, in his book Jung, Jungians, and Homosexuality, makes it easy to reference what Jung has said about homosexuality:

Fifteen references in the Collected Works, seven references in his published correspondence, two references in his autobiography, Memories, Dreams, Reflections, and a small number of references in his Dream Seminars and the interviews reported in C. G. Jung Speaking.

Hopke’s book is a rich culmination of and deep reflection on Jung’s statements about homosexuality. If you want to know more, that book is the place to go.

Jung holds no authoritative or one-sided condemnation of the phenomenon, candidly acknowledging the wide variety of relationships that are encompassed by the word homosexuality and noting the “advantages and disadvantages” of each, from the “higher and more spiritual” friendships of boys, to the educative passion between teacher and student, to the relationships of “tender feelings” and “intimate thoughts” between “high-spirited” women.

Table of Contents - Jump To Section

Carl Jung and Homosexuality in Men: It is not always an anima problem

You’ve probably heard what Jung said regarding homosexual men and the anima problem. It seems that most people talk about Jung’s idea of homosexual men only as an anima problem. But that’s not true to what Jung actually said. An anima problem in homosexual men is a distinct problem in some men.

Regarding the anima problem and homosexuality, Jung was speaking about effeminate expressions of a man’s personality, due to identification with the anima. Identification with the anima means that a man expresses himself through his anima instead of his true masculinity. This can come out in a number of different ways, for example, in a sort of feministic bitchiness or hypersensitivity. Even straight men in an anima mood act this way. Clearly, the anima problem does not apply to all homosexual men.

Carl Jung understood homosexual love and its myriad expressions. In The Love Problem of a Student (1925/28), an essay from Volume 10 of the Collected Works, he acknowledged same-sex relationships this way:

… individuals can enjoy such a rapturous friendship that they also express their feelings in sexual form. [It can be] an expression of a higher and more spiritual form of love which deserves the name “friendship” in the classical sense of the word. I am speaking here not of pathological homosexuals who are incapable of real friendship.

From the above quote, we can see that Jung clearly differentiated homosexuality as a spiritual expression and higher form of love from its pathological expressions.

Jung Homosexuality and Pathological Expressions

You should know that whenever Jung talked about homosexuality, he referred to his own case material, not to theories or personal biases. He said that he “passed no sort of moral judgment on sexuality as a natural phenomenon, but preferred to make [his] moral evaluation based on the way [homosexuality] is expressed.”

By morality, Jung did not mean conventional standards of morality, but rather an inner morality as it’s determined by an individual’s soul. It is a moral standpoint which is often expressed in our dreams and other unconscious material.

In terms of how Jung worked with homosexual patients, let’s look at another quote from Hopke’s book:

… one notices that Jung appears to follow a two-step process in working with homosexual patients, beginning with an open-minded and nonjudgmental examination of how the homosexuality is expressed in the patient’s life, followed by a moral evaluation of the homosexuality on the basis of its effect on the patient’s character or, to use the more contemporary term, personality.

For Jung homosexuality was a problem only when it was symptomatic of a problematic attitude in an individual. Here’s an example of how a problematic homosexual attitude might express itself. In my thirties, most of my friends were gay men. A man I had met through them struck me as an example of a “pathological homosexual”. To me, this guy did not come across as a homosexual man. He was not a lover of men. In fact, he acted like someone who hated men. He was really aggressive with men, both verbally and physically, and he seemed to be attracted only to men he could viciously dominate. If I had to guess, I would say this man had a problem with a cruel father.

In some women, neurotic homosexuality often couples with a hatred of men. This can sometimes damage a woman’s inherent femininity. By inherent femininity, I mean femininity as a biologically expressed archetype, not a socially constructed stereotype. There is a difference.

Carl Jung on the Problem of Love

Love is Love, Alex Thomas

For Jung, our most intimate relationships concern the “problem of love”. Using the word problem only means that whatever we are talking about is something we need to work out for ourselves. For example, we talk about the problem of consciousness or the problem of evil. We must come to terms with such problems on our own ground.

For Jung, sexuality, in whatever form it takes, concerns a problem of love.

Love is always a problem, whatever our age may be. In childhood, the love of one’s parents is a problem, and for the old man the problem is what he has made of his love. Love is a force of destiny whose power reaches from heaven to hell. We must understand love in this way if we are to do any sort of justice to the problems it involves…

C. G. Jung, The Love Problem of a Student

Carl Jung and His Views on Homosexuality

Gay Pride gallery

A man’s wholeness, in so far as he is not constitutionally homosexual, can only be a masculine personalityCarl JungTo repeat what has already been said, for Carl Jung homosexuality was not a mental illness to be remedied through analysis. He believed homosexuality could be neurotic for some men, but certainly not for all homosexual men. But even so, a homosexual neurosis is certainly not a mental illness or disorder.

Remember, according to Carl Jung homosexuality could also be a genuine higher form of love with both a spiritual and a cultural purpose.

Before I elaborate, keep something in mind from the outset. In terms of neurotic homosexuality, we aren’t talking about anyone who is in a loving, peaceful homosexual relationship. We are talking about problematic homosexual relationships and the most common psychodynamics manifested in those relationships (according to Carl Jung’s experiences with his patients). Jung imposed no homosexual preconceptions or theories on anyone.

Jung believed homosexuality in men could be genuine, and when it was genuine, it served both a spiritual and cultural purpose. By genuine, he meant “true to the nature of an individual manMarie Louise von Franz

In reference to Jung’s thoughts about male homosexuality, many people quote only what he said regarding the anima problem or a mother complex. You can find examples in the essays on the Anima, the Kore in volume 9i, Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious, some of which I will reference below.

He actually said homosexuality was an anima problem only when a man is “not constitutionally homosexual”. This is very clear in meaning, yet no one seems to notice it. Jung thought some men were constitutionally homosexual. That’s an important distinction if you’re going to point out an anima problem in homosexuality. Naturally, that begs the question, what is constitutional homosexuality? We’ll look more into that later on in an example from Marie-Louise von Franz.

Carl Jung Homosexuality in Women

Sappho and Erinna in a Garden at Mytilene 1864 Simeon Solomon 1840-1905

Compared to homosexuality in men as a possible educative or spiritual factor, here’s what Jung said about homosexuality women:

the difference in age and the educative factor are not so important. The main value lies in the exchange of tender feelings on the one hand and of intimate thoughts on the other. Generally they are high-spirited, intellectual, and [often] rather masculine women, seeking to maintain their superiority and to defend themselves against men. Their attitude to men is therefore one of disconcerting self-assurance, with a trace of defiance. Its effect on their character is to reinforce their masculine traits and to destroy their feminine charm. Often a man discovers their homosexuality only when he notices that these women leave him stone-cold.

Normally, the practice of homosexuality is not prejudicial to later heterosexual activity. Indeed, the two can even exist side by side. I know a very intelligent woman who spent her whole life as a homosexual and then at fifty entered into a relationship with a man.

Remember the age and time he wrote that. Certainly he would have something different to say today. The Spirt of the Times is not the same today as it was then.

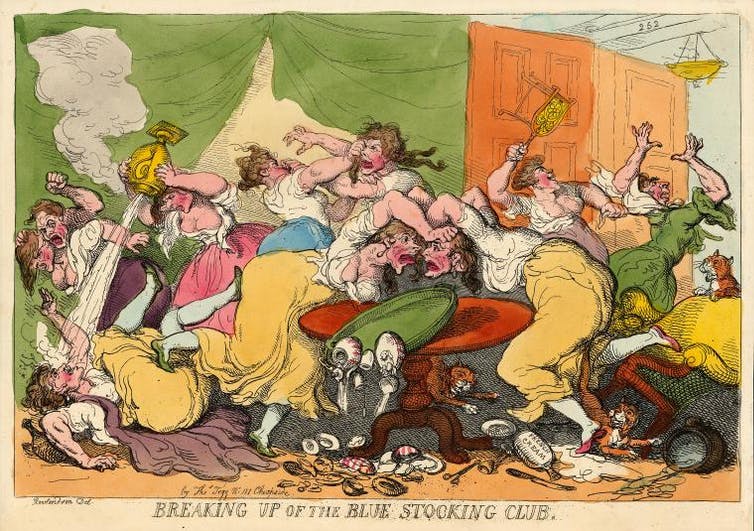

Jung, Homosexuality in Women and Problematic Relations with Each Other

In women, Jung also said neurotic homosexuality often had to do with either a mother problem or a traumatic relationship with the masculine. Remember though, Jung worked with women who came to him because they were suffering. This applies only to homosexual women who were not at peace with themselves and thus tend to have serial problematic relationships.

In women, Jung also said neurotic homosexuality often had to do with either a mother problem or a traumatic relationship with the masculine. Remember though, Jung worked with women who came to him because they were suffering. This applies only to homosexual women who were not at peace with themselves and thus tend to have serial problematic relationships.

In Volume 7 of his Collected Works, Jung recounts the story of one of his patients:

A woman patient, who had just reached the critical borderline between the analysis of the personal unconscious and the emergence of contents from the collective unconscious, had the following dream. She is about to cross a wide river. There is no bridge, but she finds a ford where she can cross. She is on the point of doing so, when a large crab that lay hidden in the water seizes her by the foot and will not let her go. She wakes up in terror.

The homosexual aspect of this woman’s dream showed up in her associations with a female friend, with whom she often fought as a man and his wife would.

There is something peculiar about her relations with this friend. It is a sentimental attachment, bordering on the homosexual, that has lasted for years. The friend is like the patient in many ways, and equally nervy. They have marked artistic interests in common. The patient is the stronger personality of the two. Because their mutual relationship is too intimate and excludes too many of the other possibilities of life, both are nervy and, despite their ideal friendship, have violent scenes due to mutual irritability.

The unconscious is trying in this way to put a distance between them, but they refuse to listen. The quarrel usually begins because one of them finds that she is still not sufficiently understood, and urges that they should speak more plainly to one another; whereupon both make enthusiastic efforts to unbosom themselves. Naturally a misunderstanding comes about in next to no time, and a worse scene than ever ensues. Faute de mieux, this quarrelling had long been for both of them a pleasure substitute which they were unwilling to relinquish.

My patient in particular could not do without the sweet pain of being misunderstood by her best friend, although every scene “tired her to death.” She had long since realized that this friendship had become moribund, and that only false ambition led her to believe that something ideal could still be made of it. She had formerly had an exaggerated, fantastic relation to her mother and after her mother’s death had transferred her feelings to her friend.

Carl Jung Homosexuality in Men: A Higher Form of Love

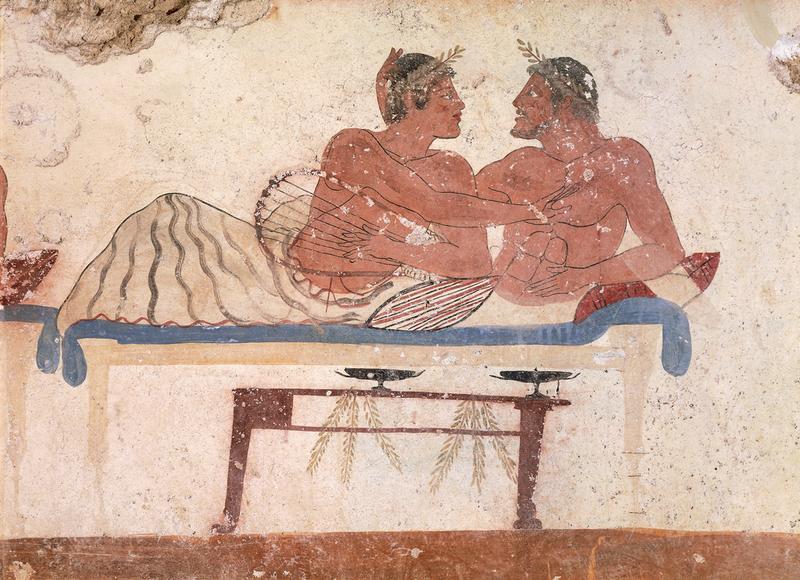

The Sacred Band of Thebes Symposium scene, ca 480-490 BC, decorative fresco from the north wall of the Tomb of the Diver at Paestum, Italy. Source: (Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Archaeological Museum)

We glean the best information about what Jung really thought or felt (about anything) from his seminars and personal letters and from conversations with those who knew him.

For example, in a question and answer session with Marie-Louise von Franz, one of his closest confidants and colleagues, someone asked her about Jung’s perspective on homosexuality.

Von Franz said Jung told her that once a homosexual man tried to convince him that homosexual love in men was the highest form of love.

To which Jung responded, “Yes I agree with you, but you see for me, it is more fun with women.”

You cannot get any more forthright than that! Jung agreed that homosexuality in men could be a higher form of love.

Quoting Von Franz again,

Jung believed there was a genuine homosexuality in men, that some men were born genuinely homosexual and that it was meant for them to be so. It would be wrong to want to make them into heterosexuals. It is their destiny and those men generally have some cultural task to fulfill. And in that case, one should not discourage their homosexuality…

Carl Jung Homosexuality: Case Studies

Von Franz had no agenda for this man, other than exploring with him, what homosexuality meant for his soul. The analysis lasted for only a few sessions. His dreams pointed to the fact of genuine homosexuality. The man he loved for many years was his true partner. And then she sent him on his way…

This is the thing about dreams. If you are really suffering over a particular problem and willing to subject that problem to analysis, then your dreams will show you exactly what you need to see.

The question is always whether or not we have the courage to accept the message our dreams.

Carl Jung Homosexuality as a Stage in a Man’s Development

Jung also spoke of young men going through homosexual phases. In that case, he used examples in primitive initiation cultures and ancient Greek and Anglo-Saxon cultures.

The onrush of sexuality in a boy brings about a powerful change in soul of a child. . . . The psychic assimilation of the sexual complex causes him the greatest difficulties even though he may not be conscious of its existence. … At this age, the young man is full of illusions, which are always a sign of psychic disequilibrium. They make stability and maturity of judgment impossible. . . . He is so riddled with illusions that he actually needs these mistakes to make him conscious of his own taste and individual judgment. He is still experimenting with life and must experiment with it in order to learn how to judge things correctly. Hence there are very few men who have not had sexual experiences before they are married. During puberty it is mostly homosexual experiences, and these are much more common than generally admitted.

Heterosexual experiences come later, not always of a very beautiful kind

These phases are a normal part of masculine maturation. The homosexual phase helps to integrate the unconscious masculine components of the personality.

Carl Jung Homosexuality: The Anima Problem

As opposed to constitutional homosexuality, Jung described neurotic homosexuality. The anima problem plays a role in neurotic homosexuality.

By neurotic, Jung simply meant someone not at one with himself. For all intents and purposes, the anima problem is first, a mother-complex problem. Here I mean something like that image in Game of Thrones, where Lysa is nursing her eight year old son. The image is so unsettling that I can’t even bring myself to post it!

Keep in mind, this image of being too-attached to the mother is also a psychological dynamic. That’s really what we mean here: unhealthy attachment to the mother. That damages a man’s relatedness to women.

A man has his anima projection in the mother first. The mother represents the female object to him. If he gets stuck in that image, then his whole feeling life, his Eros, his relatedness, his emotional experiences, his ideals along that line, are completely identified with the mother.

Dream Symbols of the Individuation Process, page 121

A man traps himself the mother-image in many ways. For example, he can be too-related to her – that is the positive-mother complex – in which case,

the disagreeable thing is that the mother then has all the real feeling of the boy, his heterosexual feeling, and what is left is only an inferior feeling for women. To him, women are either mothers or prostitutes, but not real women. Or even this adaptation to the woman may be too difficult. Then there is nothing left for him but to become a homosexual.

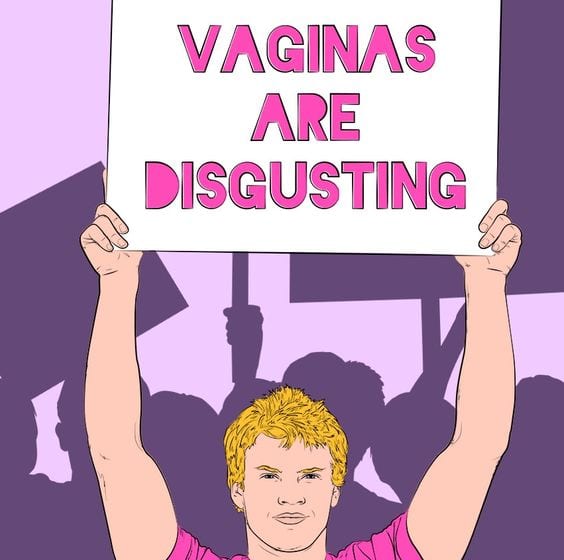

Hysterical Men: the Vagina Haters

A negative mother complex can have the opposite effect, constellating in a man, a certain revulsion toward women. When a man proves unable to relate to women with only fear or disgust, there could be a neurotic problem. I say could only to sound diplomatic …

A negative mother complex can have the opposite effect, constellating in a man, a certain revulsion toward women. When a man proves unable to relate to women with only fear or disgust, there could be a neurotic problem. I say could only to sound diplomatic …

I think we can see this neurotic problem in gay men who act hysterically (pun emphatically intended) about vaginas. For anyone who does not already know this, the word hysteria originates from the Greek word “uterus,” hystera.

Men can love other men without the neurotic element of freaking out about – or even worse, hating – a woman’s vagina.

So, if that’s you … well, then I am sorry to say, you’re acting neurotically. That doesn’t necessarily mean that you aren’t “constitutionally” homosexual. However, if your homosexuality comes with a hateful, negative attitude toward women, then it’s problematic. I realize that some men weave their self-concept into their histrionic hysteria about women, as if they are expressing their homosexuality that way.

Arguably, it can be funny. But it’s an old joke and if you are still telling it, then you are unoriginal. Maybe come up with a new show? Perhaps one that isn’t based in hate or disgust by another human being’s natural presence?

Conclusion Carl Jung Homosexuality

In the last analysis, we question whether or not, according to Jungian analysis, an individual’s homosexuality is constitutional or neurotic. When in doubt, that question can only be objectively answered through dreams and fantasies. And should we get an answer from dreams, one must be courageous enough to see it.